wikipedia Chomsky hierarchy

In the formal languages of computer science and linguistics, the Chomsky hierarchy (occasionally referred to as the Chomsky–Schützenberger hierarchy) is a containment hierarchy of classes of formal grammars.

This hierarchy of grammars was described by Noam Chomsky in 1956. It is also named after Marcel-Paul Schützenberger, who played a crucial role in the development of the theory of formal languages.

The hierarchy

The following table summarizes each of Chomsky's four types of grammars, the class of language it generates, the type of automaton that recognizes it, and the form its rules must have.

| Grammar | Languages | Automaton | Production rules (constraints)* | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type-0 | Recursively enumerable | Turing machine | $ \alpha A\beta \rightarrow \delta $ (no constraints) | $ L={w |

| Type-1 | Context-sensitive | Linear-bounded non-deterministic Turing machine | $ \alpha A\beta \rightarrow \alpha \gamma \beta $ | $ L={a{n}b{n}c^{n} |

| Type-2 | Context-free | Non-deterministic pushdown automaton | $ A\rightarrow \alpha $ | $ L={a{n}b{n} |

| Type-3 | Regular | Finite state automaton | $ A\rightarrow {\text{a}} $ and $ A\rightarrow {\text{a}}B $ | $ L={a^{n} |

Meaning of symbols:

- $ {\text{a}} $ = terminal

- $ A $, $ B $ = non-terminal

- $ \alpha $, $ \beta $, $ \gamma $, $ \delta $ = string of terminals and/or non-terminals

- $ \alpha $, $ \beta $, $ \delta $ = maybe empty

- $ \gamma $ = never empty

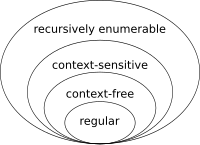

Set inclusions described by the Chomsky hierarchy

Note that the set of grammars corresponding to recursive languages is not a member of this hierarchy; these would be properly between Type-0 and Type-1.

Every regular language is context-free, every context-free language is context-sensitive, every context-sensitive language is recursive and every recursive language is recursively enumerable. These are all proper inclusions, meaning that there exist recursively enumerable languages that are not context-sensitive, context-sensitive languages that are not context-free and context-free languages that are not regular.

Type-0 grammars

Main article: Unrestricted grammar

Type-0 grammars include all formal grammars. They generate exactly all languages that can be recognized by a Turing machine. These languages are also known as the recursively enumerable or Turing-recognizable languages. Note that this is different from the recursive languages, which can be decided by an always-halting Turing machine.

Type-1 grammars

Main article: Context-sensitive grammar

Type-1 grammars generate context-sensitive languages. These grammars have rules of the form $ \alpha A\beta \rightarrow \alpha \gamma \beta $ with $ A $ a nonterminal and $ \alpha $, $ \beta $ and $ \gamma $ strings of terminals and/or nonterminals. The strings $ \alpha $ and $ \beta $ may be empty, but $ \gamma $ must be nonempty. The rule $ S\rightarrow \epsilon $ is allowed if $ S $ does not appear on the right side of any rule. The languages described by these grammars are exactly all languages that can be recognized by a linear bounded automaton (a nondeterministic Turing machine whose tape is bounded by a constant times the length of the input.)

Type-2 grammars

Main article: Context-free grammar

Type-2 grammars generate the context-free languages. These are defined by rules of the form $ A\rightarrow \alpha $ with $ A $ being a nonterminal and $ \alpha $ being a string of terminals and/or nonterminals. These languages are exactly all languages that can be recognized by a non-deterministic pushdown automaton. Context-free languages—or rather its subset of deterministic context-free language—are the theoretical basis for the phrase structure of most programming languages, though their syntax also includes context-sensitive name resolution due to declarations and scope. Often a subset of grammars is used to make parsing easier, such as by an LL parser.

Type-3 grammars

Main article: Regular grammar

Type-3 grammars generate the regular languages. Such a grammar restricts its rules to a single nonterminal on the left-hand side and a right-hand side consisting of a single terminal, possibly followed by a single nonterminal (right regular). Alternatively, the right-hand side of the grammar can consist of a single terminal, possibly preceded by a single nonterminal (left regular). These generate the same languages. However, if left-regular rules and right-regular rules are combined, the language need no longer be regular. The rule $ S\rightarrow \epsilon $ is also allowed here if $ S $ does not appear on the right side of any rule. These languages are exactly all languages that can be decided by a finite state automaton. Additionally, this family of formal languages can be obtained by regular expressions. Regular languages are commonly used to define search patterns and the lexical structure of programming languages.