wikipedia LL parser

In computer science, an LL parser (**L**eft-to-right, **L**eftmost derivation) is a top-down parser for a subset of context-free languages. It parses the input from **L**eft to right, performing **L**eftmost derivation of the sentence.

NOTE:

Follow the **L**eftmost derivation , you will find an detailed explanation of leftmost derivation.

An LL parser is called an LL(k) parser if it uses k tokens of lookahead when parsing a sentence. A grammar is called an LL(k) grammar if an LL(k) parser can be constructed from it. A formal language is called an LL(k) language if it has an LL(k) grammar. The set of LL(k) languages is properly contained in that of LL(k+1) languages, for each k ≥ 0. A corollary of this is that not all context-free languages can be recognized by an LL(k) parser. An LL parser is called an LL(*), or LL-regular, parser if it is not restricted to a finite number k of tokens of lookahead, but can make parsing decisions by recognizing whether the following tokens belong to a regular language (for example by means of a deterministic finite automaton).

LL grammars, particularly LL(1) grammars, are of great practical interest, as parsers for these grammars are easy to construct, and many computer languages are designed to be LL(1) for this reason.[3] LL parsers are table-based parsers, similar to LR parsers. LL grammars can also be parsed by recursive descent parsers. According to Waite and Goos (1984), LL(k) grammars were introduced by Stearns and Lewis (1969).

Overview

For a given context-free grammar, the parser attempts to find the leftmost derivation. Given an example grammar $ G $:

1、$ S\to E $

2、$ E\to (E+E) $

3、$ E\to i $

the leftmost derivation for $ w=((i+i)+i) $ is:

$ S {\overset {(1)}{\Rightarrow }} E {\overset {(2)}{\Rightarrow }} (E+E) {\overset {(2)}{\Rightarrow }} ((E+E)+E) {\overset {(3)}{\Rightarrow }} ((i+E)+E) {\overset {(3)}{\Rightarrow }} ((i+i)+E) {\overset {(3)}{\Rightarrow }} ((i+i)+i) $

Generally, there are multiple possibilities when selecting a rule to expand the leftmost non-terminal. In step 2 of the previous example, the parser must choose whether to apply rule 2 or rule 3:

$ S {\overset {(1)}{\Rightarrow }} E {\overset {(?)}{\Rightarrow }} ? $

To be efficient, the parser must be able to make this choice deterministically when possible, without backtracking. For some grammars, it can do this by peeking on the unread input (without reading). In our example, if the parser knows that the next unread symbol is $ ( $ , the only correct rule that can be used is 2.

NOTE: Peeking makes the parser predictive to choose an deterministic production and avoid choosing by backtracking. As you will see later, it is not enough to achieve predictability just by peeking , parsing table is also needed to make the parser predictive to avoid backtracking.

Generally, an $ LL(k) $ parser can look ahead at $ k $ symbols. However, given a grammar, the problem of determining if there exists a $ LL(k) $ parser for some $ k $ that recognizes it is undecidable. For each $ k $, there is a language that cannot be recognized by an $ LL(k) $ parser, but can be by an $ LL(k+1) $.

We can use the above analysis to give the following formal definition:

Let $ G $ be a context-free grammar and $ k\geq 1 $. We say that $ G $ is $ LL(k) $, if and only if for any two leftmost derivations:

- $ S \Rightarrow \dots \Rightarrow wA\alpha \Rightarrow \dots \Rightarrow w\beta \alpha \Rightarrow \dots \Rightarrow wu $

- $ S \Rightarrow \dots \Rightarrow wA\alpha \Rightarrow \dots \Rightarrow w\gamma \alpha \Rightarrow \dots \Rightarrow wv $

the following condition holds: the prefix of the string $ u $ of length $ k $ equals the prefix of the string $ v $ of length $ k $ implies $ \beta = \gamma $.

Do not understand.

Parser

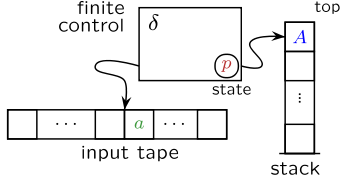

The $ LL(k) $ parser is a deterministic pushdown automaton with the ability to peek on the next $ k $ input symbols without reading. This peek capability can be emulated by storing the lookahead buffer contents in the finite state space, since both buffer and input alphabet are finite in size. As a result, this does not make the automaton more powerful, but is a convenient abstraction.

The stack alphabet is $ \Gamma =N\cup \Sigma $, where:

- $ N $ is the set of non-terminals;

- $ \Sigma $ the set of terminal (input) symbols with a special end-of-input (EOI) symbol $ $ $.

The parser stack initially contains the starting symbol above the EOI: $ [ S $ ] $. During operation, the parser repeatedly replaces the symbol $ X $ on top of the stack:

- with some $ \alpha $, if $ X\in N $ and there is a rule $ X\to \alpha $ (X is a non-terminal);

- with $ \epsilon $ (in some notations $ \lambda $), i.e. $ X $ is popped off the stack, if $ X\in \Sigma $. In this case, an input symbol $ x $ is read and if $ x\neq X , the parser rejects the input (X$ is a terminal, which means X should equal to x).

NOTE:

At first step, X is S.

If the last symbol to be removed from the stack is the EOI, the parsing is successful; the automaton accepts via an empty stack.

The states and the transition function are not explicitly given; they are specified (generated) using a more convenient parse table instead. The table provides the following mapping:

- row: top-of-stack symbol $ X $

- column: $ |w|\leq k $ lookahead buffer contents

- cell: rule number for $ X\to \alpha $ or $ \epsilon $

If the parser cannot perform a valid transition, the input is rejected (empty cells). To make the table more compact, only the non-terminal rows are commonly displayed, since the action is the same for terminals.

NOTE:

The LL parser consists of three parts

1、parsing table

2、parser stack

3、input stream

The following image is from a Wikipedia entry pushdown automaton

The $ LL(k) $ parser is a deterministic pushdown automaton.

Concrete example

Set up

To explain an LL(1) parser's workings we will consider the following small LL(1) grammar:

- S → F

- S → ( S + F )

- F → a

and parse the following input:

( a + a )

An LL(1) parsing table for a grammar has a row for each of the non-terminals and a column for each terminal (including the special terminal, represented here as $, that is used to indicate the end of the input stream).

Each cell of the table may point to at most one rule of the grammar (identified by its number). For example, in the parsing table for the above grammar, the cell for the non-terminal 'S' and terminal '(' points to the rule number 2:

| ( | ) | a | + | $ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | 2 | - | 1 | - | - |

| F | - | - | 3 | - | - |

The algorithm to construct a parsing table is described in a later section, but first let's see how the parser uses the parsing table to process its input.

Parsing procedure

In each step, the parser reads the next-available symbol from the input stream, and the top-most symbol from the stack. If the input symbol and the stack-top symbol match, the parser discards them both, leaving only the unmatched symbols in the input stream and on the stack.

Thus, in its first step, the parser reads the input symbol ( and the stack-top symbol S. The parsing table instruction comes from the column headed by the input symbol ( and the row headed by the stack-top symbol S; this cell contains 2, which instructs the parser to apply rule (2). The parser has to rewrite S to ( S + F ) on the stack by removing S from stack and pushing ), F, +, S, ( onto the stack, and this writes the rule number 2 to the output. The stack then becomes:

[ (, S, +, F, ), $ ]

In the second step, the parser removes the ( from its input stream and from its stack, since they now match. The stack now becomes:

[ S, +, F, ), $ ]

Now the parser has an a on its input stream and an S as its stack top. The parsing table instructs it to apply rule (1) from the grammar and write the rule number 1 to the output stream. The stack becomes:

[ F, +, F, ), $ ]

The parser now has an 'a' on its input stream and an 'F' as its stack top. The parsing table instructs it to apply rule (3) from the grammar and write the rule number 3 to the output stream. The stack becomes:

[ a, +, F, ), $ ]

The parser now has an 'a' on the input stream and an 'a' at its stack top. Because they are the same, it removes it from the input stream and pops it from the top of the stack. The parser then has an '+' on the input stream and '+' is at the top of the stack meaning, like with 'a', it is popped from the stack and removed from the input stream. This results in:

[ F, ), $ ]

In the next three steps the parser will replace 'F' on the stack by 'a', write the rule number 3 to the output stream and remove the 'a' and ')' from both the stack and the input stream. The parser thus ends with '$' on both its stack and its input stream.

In this case the parser will report that it has accepted the input string and write the following list of rule numbers to the output stream:

[ 2, 1, 3, 3 ]

This is indeed a list of rules for a leftmost derivation of the input string, which is:

S → ( S + F ) → ( F + F ) → ( a + F ) → ( a + a )

implementation

- cpp

- python

Remarks

As can be seen from the example, the parser performs three types of steps depending on whether the top of the stack is a nonterminal, a terminal or the special symbol $:

- If the top is a nonterminal then the parser looks up in the parsing table, on the basis of this nonterminal and the symbol on the input stream, which rule of the grammar it should use to replace nonterminal on the stack. The number of the rule is written to the output stream. If the parsing table indicates that there is no such rule then the parser reports an error and stops.

- If the top is a terminal then the parser compares it to the symbol on the input stream and if they are equal they are both removed. If they are not equal the parser reports an error and stops.

- If the top is ** and on the input stream there is also a ** then the parser reports that it has successfully parsed the input, otherwise it reports an error. In both cases the parser will stop.

These steps are repeated until the parser stops, and then it will have either completely parsed the input and written a leftmost derivation to the output stream or it will have reported an error.

Constructing an LL(1) parsing table

In order to fill the parsing table, we have to establish what grammar rule the parser should choose if it sees a nonterminal A on the top of its stack and a symbol a on its input stream. It is easy to see that such a rule should be of the form A → w and that the language corresponding to w should have at least one string starting with a. For this purpose we define the First-set of w, written here as Fi (w), as the set of terminals that can be found at the start of some string in w, plus \epsilon if the empty string also belongs to w. Given a grammar with the rules A_1 \to w_1, \dots, A_n \to w_n, we can compute the Fi (wi) and Fi (Ai) for every rule as follows: