preshing Atomic vs. Non-Atomic Operations

NOTE: 这篇文章写得非常好

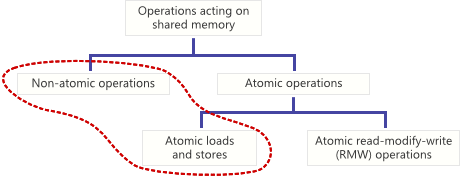

Much has already been written about atomic operations on the web, usually with a focus on atomic read-modify-write (RMW) operations. However, those aren’t the only kinds of atomic operations. There are also atomic loads and stores, which are equally important. In this post, I’ll compare atomic loads and stores to their non-atomic counterparts at both the processor level and the C/C++ language level. Along the way, we’ll clarify the C++11 concept of a “data race”.

An operation acting on shared memory is atomic if it completes in a single step relative to other threads(从线程的角度来看待atomic). When an atomic store is performed on a shared variable, no other thread can observe the modification half-complete. When an atomic load is performed on a shared variable, it reads the entire value as it appeared at a single moment in time. Non-atomic loads and stores do not make those guarantees.

Without those guarantees, lock-free programming would be impossible, since you could never let different threads manipulate a shared variable at the same time. We can formulate it as a rule:

Any time two threads operate on a shared variable concurrently, and one of those operations performs a write, both threads must use atomic operations.

NOTE: 上面这些都是可以使用multiple-model来进行分析的,尤其是从read-write的角度来进行分析的

If you violate this rule, and either thread uses a non-atomic operation, you’ll have what the C++11 standard refers to as a data race (not to be confused with Java’s concept of a data race, which is different, or the more general race condition). The C++11 standard doesn’t tell you why data races are bad; only that if you have one, “undefined behavior” will result (§1.10.21). The real reason why such data races are bad is actually quite simple: They result in torn reads and torn writes.

NOTE: "torn"的意思是"撕裂的"

A memory operation can be non-atomic because it uses multiple CPU instructions, non-atomic even when using a single CPU instruction, or non-atomic because you’re writing portable code and you simply can’t make the assumption. Let’s look at a few examples.

Non-Atomic Due to Multiple CPU Instructions

Suppose you have a 64-bit global variable, initially zero.

uint64_t sharedValue = 0;

At some point, you assign a 64-bit value to this variable.

void storeValue()

{

sharedValue = 0x100000002;//16进制

}

When you compile this function for 32-bit x86 using GCC, it generates the following machine code.

NOTE: 需要注意的是:

uint64_t是64-bit,实验环境是: 32-bit

$ gcc -O2 -S -masm=intel test.c

$ cat test.s

...

mov DWORD PTR sharedValue, 2

mov DWORD PTR sharedValue+4, 1

ret

...

As you can see, the compiler implemented the 64-bit assignment using two separate machine instructions. The first instruction sets the lower 32 bits to 0x00000002, and the second sets the upper 32 bits to 0x00000001. Clearly, this assignment operation is not atomic. If sharedValue is accessed concurrently by different threads, several things can now go wrong:

1、If a thread calling storeValue is preempted between the two machine instructions, it will leave the value of 0x0000000000000002 in memory – a torn write. At this point, if another thread reads sharedValue, it will receive this completely bogus(伪造的) value which nobody intended to store.

NOTE: 如果调用

storeValue的线程在两个机器指令之间被抢占,它将在内存中保留0x0000000000000002的值 - 一个撕裂的写入。 此时,如果另一个线程读取sharedValue,它将收到这个完全虚假的值,没有人打算存储。

2、Even worse, if a thread is preempted between the two instructions, and another thread modifies sharedValue before the first thread resumes, it will result in a permanently torn write: the upper 32 bits from one thread, the lower 32 bits from another.

NOTE: 更糟糕的是,如果一个线程在两个指令之间被抢占,而另一个线程在第一个线程恢复之前修改了

sharedValue,则会导致永久性的写入:一个线程的高32位,另一个低32位(第一个线程先写入的一半内容会被第二个线程覆盖,然后第一个线程resume后,它会写入后半部分,这就覆盖了第二个线程之前写入的内容,显然它们相互覆盖,导致了最终各自都只写入了一半)

3、On multicore devices, it isn’t even necessary to preempt one of the threads to have a torn write. When a thread calls storeValue, any thread executing on a different core could read sharedValue at a moment when only half the change is visible.

NOTE: 显然,multicore的情况下,可能每个thread会占用一个core,但是它们共享process的memory,它们能够同时access process的memory中的同一个地址;如果它们对shared memory的access不按照互斥原则来进行,即每次在access shared memory之前,先lock;则就会导致对shared memory的access是无序的;显然互斥原则即能够保证在multicore情况下的安全,也保证了在single core情况下,即使preempted,也能够安全;

Reading concurrently from sharedValue brings its own set of problems:

uint64_t loadValue()

{

return sharedValue;

}

$ gcc -O2 -S -masm=intel test.c

$ cat test.s

...

mov eax, DWORD PTR sharedValue

mov edx, DWORD PTR sharedValue+4

ret

...

Here too, the compiler has implemented the load operation using two machine instructions: The first reads the lower 32 bits into eax, and the second reads the upper 32 bits into edx. In this case, if a concurrent store to sharedValue becomes visible between the two instructions, it will result in a torn read – even if the concurrent store was atomic.

NOTE: 上面这段话的意思是在两个machine instruction之间,另外一个线程write to

sharedValue,这就导致之前read的值是一半一半的;

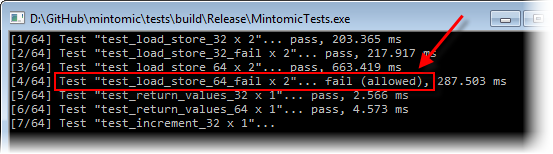

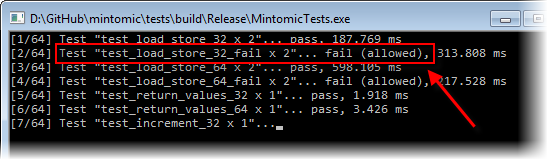

These problems are not just theoretical. Mintomic’s test suite includes a test case called test_load_store_64_fail, in which one thread stores a bunch of 64-bit values to a single variable using a plain assignment operator, while another thread repeatedly performs a plain load from the same variable, validating each result. On a multicore x86, this test fails consistently, as expected.

Non-Atomic CPU Instructions

A memory operation can be non-atomic even when performed by a single CPU instruction. For example, the ARMv7 instruction set includes the strd instruction, which stores the contents of two 32-bit source registers to a single 64-bit value in memory.

strd r0, r1, [r2]

On some ARMv7 processors, this instruction is not atomic. When the processor sees this instruction, it actually performs two separate 32-bit stores under the hood (§A3.5.3). Once again, another thread running on a separate core has the possibility of observing a torn write. Interestingly, a torn write is even possible on a single-core device: A system interrupt – say, for a scheduled thread context switch – can actually occur between the two internal 32-bit stores! In this case, when the thread resumes from the interrupt, it will restart the strd instruction all over again.

As another example, it’s well-known that on x86, a 32-bit mov instruction is atomic if the memory operand is naturally aligned, but non-atomic otherwise. In other words, atomicity is only guaranteed when the 32-bit integer is located at an address which is an exact multiple of 4. Mintomic comes with another test case, test_load_store_32_fail, which verifies this guarantee. As it’s written, this test always succeeds on x86, but if you modify the test to force sharedInt to certain unaligned addresses, it will fail. On my Core 2 Quad Q6600, the test fails when sharedInt crosses a cache line boundary:

// Force sharedInt to cross a cache line boundary:

#pragma pack(2)

MINT_DECL_ALIGNED(static struct, 64)

{

char padding[62];

mint_atomic32_t sharedInt;

}

g_wrapper;

Those are enough processor-specific details for now. Let’s look at atomicity at the C/C++ language level.

NOTE:

movis not atomic的情况还没有搞懂,需要Google:movis not atomic when address is not aligned

All C/C++ Operations Are Presumed(假定) Non-Atomic

In C and C++, every operation is presumed non-atomic unless otherwise specified by the compiler or hardware vendor – even plain 32-bit integer assignment.

uint32_t foo = 0;

void storeFoo()

{

foo = 0x80286;

}

The language standards have nothing to say about atomicity in this case. Maybe integer assignment is atomic, maybe it isn’t. Since non-atomic operations don’t make any guarantees, plain integer assignment in C is non-atomic by definition.

In practice, we usually know more about our target platforms than that. For example, it’s common knowledge that on all modern x86, x64, Itanium, SPARC, ARM and PowerPC processors, plain 32-bit integer assignment is atomic as long as the target variable is naturally aligned. You can verify it by consulting your processor manual and/or compiler documentation. In the games industry, I can tell you that a lot of 32-bit integer assignments rely on this particular guarantee.

NOTE: 上面这段话让我想起来alignment的重要价值

Nonetheless(尽管如此), when writing truly portable C and C++, there’s a long-standing tradition of pretending that we don’t know anything more than what the language standards tell us. Portable C and C++ is designed to run on every possible computing device past, present and imaginary (这句话说明了portable的含义).

NOTE: 上面在这段话,其实总结了书写cross-plateform/portable C and C++ program的精神要义: 对于 language standards 未进行标准化的,我们应该假装不知道,即不做任何假设。

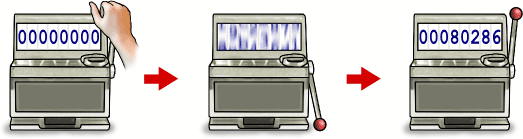

Personally, I like to imagine a machine where memory can only be changed by mixing it up first:

On such a machine, you definitely wouldn’t want to perform a concurrent read at the same time as a plain assignment; you could end up reading a completely random value.

In C++11, there is finally a way to perform truly portable atomic loads and stores: the C++11 atomic library. Atomic loads and stores performed using the C++11 atomic library would even work on the imaginary computer above – even if it means the C++11 atomic library must secretly lock a mutex to make each operation atomic. There’s also the Mintomic library which I released last month, which doesn’t support as many platforms, but works on several older compilers, is hand-optimized and is guaranteed to be lock-free.

NOTE: C++11 atomic library对atomic load、store进行了标准化。

Relaxed Atomic Operations

Let’s return to the original sharedValue example from earlier in this post. We’ll rewrite it using Mintomic so that all operations are performed atomically on every platform Mintomic supports. First, we must declare sharedValue as one of Mintomic’s atomic data types.

#include <mintomic/mintomic.h>

mint_atomic64_t sharedValue = { 0 };

The mint_atomic64_t type guarantees correct memory alignment for atomic access on each platform. This is important because, for example, the GCC 4.2 compiler for ARM bundled with Xcode 3.2.5 doesn’t guarantee that plain uint64_t will be 8-byte aligned.

In storeValue, instead of performing a plain, non-atomic assignment, we must call mint_store_64_relaxed.

void storeValue()

{

mint_store_64_relaxed(&sharedValue, 0x100000002);

}

Similarly, in loadValue, we call mint_load_64_relaxed.

uint64_t loadValue()

{

return mint_load_64_relaxed(&sharedValue);

}

Using C++11’s terminology, these functions are now data race-free. When executing concurrently, there is absolutely no possibility of a torn read or write, whether the code runs on ARMv6/ARMv7 (Thumb or ARM mode), x86, x64 or PowerPC. If you’re curious how mint_load_64_relaxed and mint_store_64_relaxed actually work, both functions expand to an inline cmpxchg8b instruction on x86; for other platforms, consult Mintomic’s implementation.

Here’s the exact same thing written in C++11 instead:

#include <atomic>

std::atomic<uint64_t> sharedValue(0);

void storeValue()

{

sharedValue.store(0x100000002, std::memory_order_relaxed);

}

uint64_t loadValue()

{

return sharedValue.load(std::memory_order_relaxed);

}

You’ll notice that both the Mintomic and C++11 examples use relaxed atomics, as evidenced by the _relaxed suffix on various identifiers. The _relaxed suffix is a reminder that few guarantees are made about memory ordering.

In particular, it is still legal for the memory effects of a relaxed atomic operation to be reordered with respect to instructions which follow or precede it in program order, either due to compiler reordering or memory reordering on the processor itself. The compiler could even perform optimizations on redundant relaxed atomic operations, just as with non-atomic operations. In all cases, the operation remains atomic.

When manipulating shared memory concurrently, I think it’s good practice to always use Mintomic or C++11 atomic library functions, even in cases where you know that a plain load or store would already be atomic on your target platform. An atomic library function serves as a reminder that elsewhere, the variable is the target of concurrent data access.

Hopefully, it’s now a bit more clear why the World’s Simplest Lock-Free Hash Table uses Mintomic library functions to manipulate shared memory concurrently from different threads.

THINKING :

how does compiler ensure alignment

Coding for Performance: Data alignment and structures

Data Structure Alignment : Linker or Compiler