preshing Locks Aren't Slow; Lock Contention Is

NOTE:

Locks (also known as mutexes) have a history of being misjudged(被误判). Back in 1986, in a Usenet discussion on multithreading, Matthew Dillon wrote, “Most people have the misconception that locks are slow.” 25 years later, this misconception still seems to pop up once in a while.

It’s true that locking is slow on some platforms, or when the lock is highly contended. And when you’re developing a multithreaded application, it’s very common to find a huge performance bottleneck caused by a single lock. But that doesn’t mean all locks are slow. As I’ll show in this post, sometimes a **locking strateg**y achieves excellent performance.

NOTE: lock是为了实现Mutual-exclusion,不同的lock,采用不同的locking strategy、运行机制,这导致它们的performance也不同,programmer需要根据自己的需求来选择lock; 无论选择哪种lock方式,当lock被占用的时候,它都需要wait,这就是Lock Contention,在后面的"Lock Contention Benchmark"章节中,给出了definition;不同的lock,实现wait的机制也是不同的;显然导致lock contention是slow的原因;

如果使用kernel mutex,则当发生Lock Contention的时候,OS 通常会将thread block,然后当可用的时候,再将它唤醒,相比之下,这个过程是比较缓慢的;

因此,这篇文章其实主要是在对比kernel mutex和light weight mutex;

Perhaps the most easily-overlooked source of this misconception: Not all programmers may be aware of the difference between a lightweight mutex and a “kernel mutex”. I’ll talk about that in my next post, Always Use a Lightweight Mutex. For now, let’s just say that if you’re programming in C/C++ on Windows, the Critical Section object is the one you want.

NOTE: light weight mutex和kernel mutex是作者主要进行对比的内容

Other times, the conclusion that locks are slow is supported by a benchmark. For example, this post measures the performance of a lock under heavy conditions: each thread must hold the lock to do any work (high contention), and the lock is held for an extremely short interval of time (high frequency). It’s a good read, but in a real application, you generally want to avoid using locks in that way. To put things in context, I’ve devised a benchmark which includes both best-case and worst-case usage scenarios for locks.

NOTE: 在high contention、high frequency的情况下,使用lock,则非常容易发生lock contention。

Locks may be frowned upon for other reasons. There’s a whole other family of techniques out there known as lock-free (or lockless) programming. Lock-free programming is extremely challenging, but delivers huge performance gains in a lot of real-world scenarios. I know programmers who spent days, even weeks fine-tuning a lock-free algorithm, subjecting it to a battery of tests, only to discover hidden timing bugs several months later. The combination of danger and reward can be very enticing to a certain kind of programmer – and this includes me, as you’ll see in future posts! With lock-free techniques beckoning us to use them, locks can begin to feel boring, slow and busted.

NOTE: 第一句话"Locks may be frowned upon for other reasons."的意思是: lock有诸多缺点,因此出现了lockless programming。虽然lock有着诸多缺点,但是并不是说它是一无是处的,在下一段中,作者给出了需要使用lock的情况

But don’t disregard(忽视) locks yet. One good example of a place where locks perform admirably(极好的), in real software, is when protecting the memory allocator. Doug Lea’s Malloc is a popular memory allocator in video game development, but it’s single threaded, so we need to protect it using a lock. During gameplay, it’s not uncommon to see multiple threads hammering(捶打,此处引申义: 使用、调用) the memory allocator, say around 15000 times per second. While loading, this figure can climb to 100000 times per second or more. It’s not a big problem, though. As you’ll see, locks handle the workload like a champ.

Lock Contention Benchmark

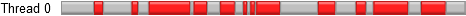

In this test, we spawn a thread which generates random numbers, using a custom Mersenne Twister implementation. Every once in a while, it acquires and releases a lock. The lengths of time between acquiring and releasing the lock are random, but they tend towards average values which we decide ahead of time. For example, suppose we want to acquire the lock 15000 times per second, and keep it held 50% of the time. Here’s what part of the timeline would look like. Red means the lock is held, grey means it’s released:

This is essentially a Poisson process(泊松过程). If we know the average amount of time to generate a single random number – 6.349 ns on a 2.66 GHz quad-core Xeon – we can measure time in work units, rather than seconds. We can then use the technique described in my previous post, How to Generate Random Timings for a Poisson Process, to decide how many work units to perform between acquiring and releasing the lock. Here’s the implementation in C++. I’ve left out a few details, but if you like, you can download the complete source code here.

NOTE: 作者度量时间的单位是work unit,而不是second,一个work unit对应的是使用Poisson process(泊松过程)生成一个random number,作者认为work unit的耗时是固定的;

作者进行benchmark的思路是这样的:

1、process的运行时间固定

2、一个process可以由多个thread组成,每个thread执行如下function;

3、

workDone记录了process是运行时间内完成的work unit4、通过比较work unit来对比performance

QueryPerformanceCounter(&start);

for (;;)

{

// Do some work without holding the lock

workunits = (int) (random.poissonInterval(averageUnlockedCount) + 0.5f);

for (int i = 1; i < workunits; i++)

random.integer(); // Do one work unit

workDone += workunits;

QueryPerformanceCounter(&end);

elapsedTime = (end.QuadPart - start.QuadPart) * ooFreq;

if (elapsedTime >= timeLimit)

break;

// Do some work while holding the lock

EnterCriticalSection(&criticalSection);

workunits = (int) (random.poissonInterval(averageLockedCount) + 0.5f);

for (int i = 1; i < workunits; i++)

random.integer(); // Do one work unit

workDone += workunits;

LeaveCriticalSection(&criticalSection);

QueryPerformanceCounter(&end);

elapsedTime = (end.QuadPart - start.QuadPart) * ooFreq;

if (elapsedTime >= timeLimit)

break;

}

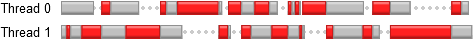

Now suppose we launch two such threads, each running on a different core. Each thread will hold the lock during 50% of the time when it can perform work, but if one thread tries to acquire the lock while the other thread is holding it, it will be forced to wait. This is known as lock contention.

NOTE: 从上述代码可以看出,实现 "50%" 的方法是非常简单的: 重复执行两次,一次不lock,一次lock

In my opinion, this is a pretty good simulation of the way a lock might be used in a real application. When we run the above scenario, we find that each thread spends roughly 25% of its time waiting, and 75% of its time doing actual work. Together, both threads achieve a net performance of 1.5x compared to the single-threaded case.

NOTE: **1.5x**是这样算出来的: 75% * 2 = 1.5

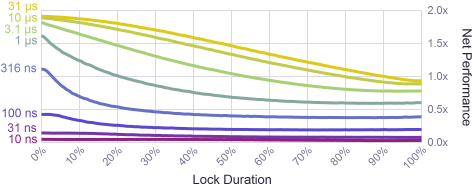

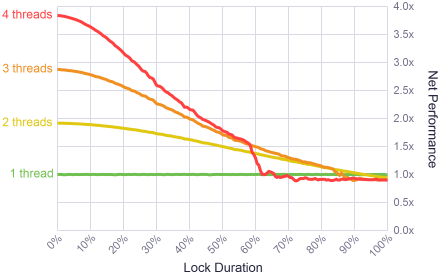

I ran several variations of the test on a 2.66 GHz quad-core Xeon, from 1 thread, 2 threads, all the way up to 4 threads, each running on its own core. I also varied the duration of the lock, from the trivial case where the the lock is never held, all the way up to the maximum where each thread must hold the lock for 100% of its workload. In all cases, the lock frequency remained constant – threads acquired the lock 15000 times for each second of work performed.

The results were interesting. For short lock durations, up to say 10%, the system achieved very high parallelism. Not perfect parallelism, but close. Locks are fast!

To put the results in perspective, I analyzed the memory allocator lock in a multithreaded game engine using this profiler. During gameplay, with 15000 locks per second coming from 3 threads, the lock duration was in the neighborhood of just 2%. That’s well within the comfort zone on the left side of the diagram.

These results also show that once the lock duration passes 90%, there’s no point using multiple threads anymore. A single thread performs better. Most surprising is the way the performance of 4 threads drops off a cliff around the 60% mark! This looked like an anomaly, so I re-ran the tests several additional times, even trying a different testing order. The same behavior happened consistently. My best hypothesis is that the experiment hits some kind of snag in the Windows scheduler, but I didn’t investigate further.

Lock Frequency Benchmark