Always Use a Lightweight Mutex

In multithreaded programming, we often speak of locks (also known as mutexes). But a lock is only a concept. To actually use that concept, you need an implementation. As it turns out, there are many ways to implement a lock, and those implementations vary wildly in performance.

NOTE: 这个观点,在上一篇的note中已经总结了,这一篇,作者对这个观点进行验证。作者使用的是Windows的

The Windows SDK provides two lock implementations for C/C++: the Mutex and the Critical Section. (As Ned Batchelder points out, Critical Section is probably not the best name to give to the lock itself, but we’ll forgive that here.)

The Windows Critical Section is what we call a lightweight mutex. It’s optimized for the case when there are no other threads competing for the lock. To demonstrate using a simple example, here’s a single thread which locks and unlocks a Windows Mutex exactly one million times.

NOTE: 上面这段话中的"It’s optimized for the case when there are no other threads competing for the lock"的意思是: 当"no other threads competing for the lock"时, Windows Critical Section 被优化了: 它不会进入kernel space

HANDLE mutex = CreateMutex(NULL, FALSE, NULL);

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++)

{

WaitForSingleObject(mutex, INFINITE);

ReleaseMutex(mutex);

}

CloseHandle(mutex);

Here’s the same experiment using a Windows Critical Section.

CRITICAL_SECTION critSec;

InitializeCriticalSection(&critSec);

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++)

{

EnterCriticalSection(&critSec);

LeaveCriticalSection(&critSec);

}

DeleteCriticalSection(&critSec);

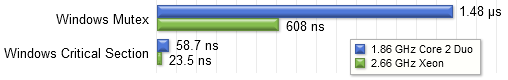

If you insert some timing code around the inner loop, and divide the result by one million, you’ll find the average time required for a pair of lock/unlock operations in both cases. I did that, and ran the experiment on two different processors. The results:

The Critical Section is 25 times faster. As Larry Osterman explains, the Windows Mutex enters the kernel every time you use it, while the Critical Section does not. The tradeoff is that you can’t share a Critical Section between processes. But who cares? Most of the time, you just want to protect some data within a single process. (It is actually possible to share a lightweight mutex between processes - just not using a Critical Section. See Roll Your Own Lightweight Mutex for example.)

NOTE: 上面这段话解释了Windows critical section优于Windows mutex的原因: **Windows Mutex**不管什么情况都进入kernel,而Critical Section 采用了更加优化的策略。

Other Platforms

In MacOS 10.6.6, a lock implementation is provided using the POSIX Threads API. It’s a lightweight mutex which doesn’t enter the kernel unless there’s contention. A pair of uncontended calls to pthread_mutex_lock and pthread_mutex_unlock takes about 92 ns on my 1.86 GHz Core 2 Duo. Interestingly, it detects when there’s only one thread running, and in that case switches to a trivial codepath taking only 38 ns.

Naturally, Ubuntu 11.10 provides a lock implementation using the POSIX Threads API as well. It’s another lightweight mutex, based on a Linux-specific construct known as a futex. A pair of pthread_mutex_lock/pthread_mutex_unlock calls takes about 66 ns on my Core 2 Duo. You can even share this implementation between processes, but I didn’t test that.

Some of you old-timers may point out ancient platforms where a heavy lock was the only implementation available, or when a semaphore had to be used for the job. But it seems all modern platforms offer a lightweight mutex. And even if they didn’t, you could write your own lightweight mutex at the application level, even sharing it between processes, provided you’re willing to live with certain caveats. You’ll find one example in my followup post, Roll Your Own Lightweight Mutex.