gotw The Free Lunch Is Over: A Fundamental Turn Toward Concurrency in Software

NOTE:

1、是在阅读 preshing A Look Back at Single-Threaded CPU Performance 时,发现的这篇文章

2、在 更好的内存管理-jemalloc (redis 默认使用的) 中,对这篇文章的核心观点进行了非常好的解读:

2005年发表了一篇文章“免费午餐的时代结束了”。在之前,程序就算不用费脑子,随着cpu时钟速度增加,程序性能自己就会上去。但现在不同,现在cpu时钟趋于稳定,而核数不断地增加。程序员需要适应这样的多线程多进程的环境,并要开发出适合的程序。文章讲的大概是这样的内容。

6年之后的如今,这篇文章完全变成现实了。事实上cpu时钟停留在3GHz,而核不断上升。现在程序要适应多线程多进程的分布式计算,速度才能上升。但是这样的程序很难。

3、非常能够体现"hardware and software-Andy and Bill's law"

4、这篇文章非常地高瞻远瞩,写于 2005 年,时至今日,依然有效。

序言

By Herb Sutter

The biggest sea change in software development since the OO revolution is knocking at the door, and its name is Concurrency.

This article appeared in *Dr. Dobb's Journal, 30(3), March 2005**. A much briefer version under the title "The Concurrency Revolution" appeared in C/C++ Users Journal, 23(2), February 2005.*

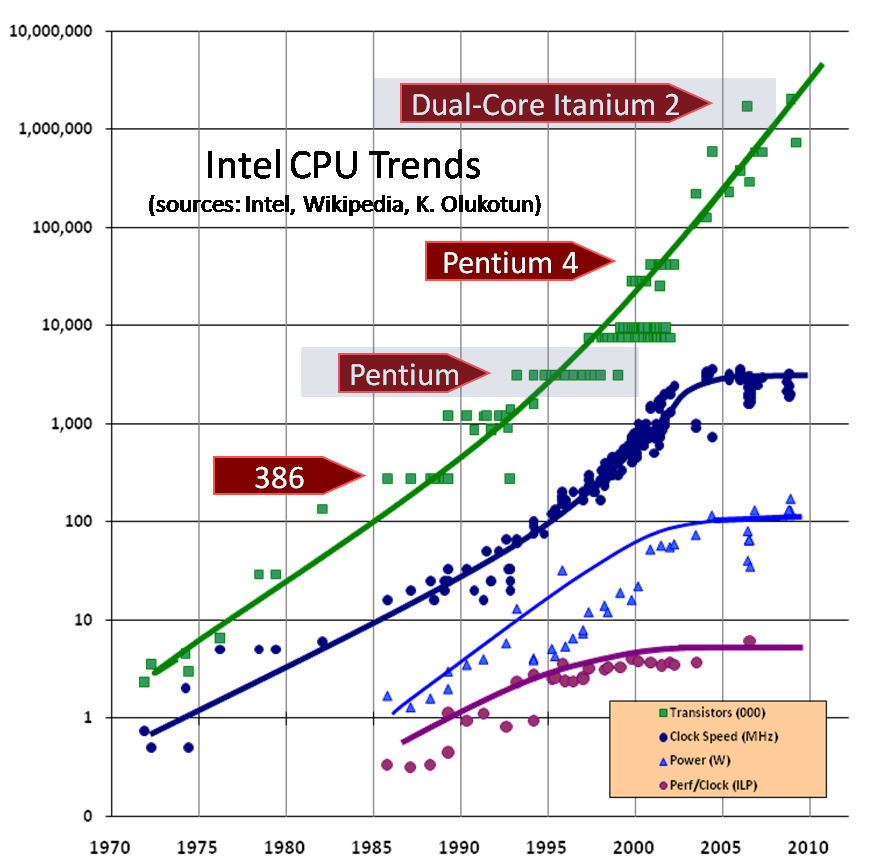

Update note: The CPU trends graph last updated August 2009 to include current data and show the trend continues as predicted. The rest of this article including all text is still original as first posted here in December 2004.

Your free lunch will soon be over. What can you do about it? What are you doing about it?

The major processor manufacturers and architectures, from Intel and AMD to Sparc and PowerPC, have run out of room with most of their traditional approaches to boosting CPU performance. Instead of driving(驱动) clock speeds and straight-line instruction throughput ever higher, they are instead turning en masse(一同地) to hyperthreading(超线程) and multicore architectures. Both of these features are already available on chips today; in particular, multicore is available on current PowerPC and Sparc IV processors, and is coming in 2005 from Intel and AMD. Indeed, the big theme of the 2004 In-Stat/MDR Fall Processor Forum was multicore devices, as many companies showed new or updated multicore processors. Looking back, it’s not much of a stretch to call 2004 the year of multicore.

And that puts us at a fundamental turning point in software development, at least for the next few years and for applications targeting general-purpose desktop computers and low-end servers (which happens to account for the vast bulk of the dollar value of software sold today). In this article, I’ll describe the changing face of hardware, why it suddenly does matter to software, and how specifically the concurrency revolution matters to you and is going to change the way you will likely be writing software in the future.

NOTE:

高瞻远瞩

Arguably, the free lunch has already been over for a year or two, only we’re just now noticing.

The Free Performance Lunch

There’s an interesting phenomenon that’s known as “Andy giveth, and Bill taketh away.” No matter how fast processors get, software consistently finds new ways to eat up the extra speed. Make a CPU ten times as fast, and software will usually find ten times as much to do (or, in some cases, will feel at liberty to do it ten times less efficiently). Most classes of applications have enjoyed free and regular performance gains for several decades, even without releasing new versions or doing anything special, because the CPU manufacturers (primarily) and memory and disk manufacturers (secondarily) have reliably enabled ever-newer and ever-faster mainstream systems. Clock speed isn’t the only measure of performance, or even necessarily a good one, but it’s an instructive one: We’re used to seeing 500MHz CPUs give way to 1GHz CPUs give way to 2GHz CPUs, and so on. Today we’re in the 3GHz range on mainstream computers.

Obstacles, and Why You Don’t Have 10GHz Today

TANSTAAFL: Moore’s Law and the Next Generation(s)

What This Means For Software: The Next Revolution

Concurrency is the next major revolution in how we write software

In the 1990s, we learned to grok objects. The revolution in mainstream software development from structured programming to object-oriented programming was the greatest such change in the past 20 years, and arguably in the past 30 years. There have been other changes, including the most recent (and genuinely interesting) naissance of web services, but nothing that most of us have seen during our careers has been as fundamental and as far-reaching a change in the way we write software as the object revolution.

Until now.

Starting today, the performance lunch isn’t free any more. Sure, there will continue to be generally applicable performance gains that everyone can pick up, thanks mainly to cache size improvements. But if you want your application to benefit from the continued exponential throughput advances in new processors, it will need to be a well-written concurrent (usually multithreaded) application. And that’s easier said than done, because not all problems are inherently parallelizable and because concurrent programming is hard.

I can hear the howls of protest: “Concurrency? That’s not news! People are already writing concurrent applications.” That’s true. Of a small fraction of developers.

Remember that people have been doing object-oriented programming since at least the days of Simula in the late 1960s. But OO didn’t become a revolution, and dominant in the mainstream, until the 1990s. Why then? The reason the revolution happened was primarily that our industry was driven by requirements to write larger and larger systems that solved larger and larger problems and exploited the greater and greater CPU and storage resources that were becoming available. OOP’s strengths in abstraction and dependency management made it a necessity for achieving large-scale software development that is economical, reliable, and repeatable.

Similarly, we’ve been doing concurrent programming since those same dark ages, writing coroutines and monitors and similar jazzy stuff. And for the past decade or so we’ve witnessed incrementally more and more programmers writing concurrent (multi-threaded, multi-process) systems. But an actual revolution marked by a major turning point toward concurrency has been slow to materialize. Today the vast majority of applications are single-threaded, and for good reasons that I’ll summarize in the next section.

By the way, on the matter of hype: People have always been quick to announce “the next software development revolution,” usually about their own brand-new technology. Don’t believe it. New technologies are often genuinely interesting and sometimes beneficial, but the biggest revolutions in the way we write software generally come from technologies that have already been around for some years and have already experienced gradual growth before they transition to explosive growth. This is necessary: You can only base a software development revolution on a technology that’s mature enough to build on (including having solid vendor and tool support), and it generally takes any new software technology at least seven years before it’s solid enough to be broadly usable without performance cliffs and other gotchas. As a result, true software development revolutions like OO happen around technologies that have already been undergoing refinement for years, often decades. Even in Hollywood, most genuine “overnight successes” have really been performing for many years before their big break.

Concurrency is the next major revolution in how we write software. Different experts still have different opinions on whether it will be bigger than OO, but that kind of conversation is best left to pundits. For technologists, the interesting thing is that concurrency is of the same order as OO both in the (expected) scale of the revolution and in the complexity and learning curve of the technology.

What It Means For Us

Applications will increasingly need to be concurrent if they want to fully exploit continuing exponential CPU throughput gains

Efficiency and performance optimization will get more, not less, important